Promoting Resilient Operations for Transformative, Efficient, and Cost-saving Transportation (PROTECT) Program Overview

The Promoting Resilient Operations for Transformative, Efficient, and Cost-saving Transportation (PROTECT) program, established under the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL), aims to enhance the resilience of surface transportation systems against natural hazards such as climate change, sea level rise, flooding, and extreme weather events. The program includes both formula and discretionary grants to support resilience planning, improvements, community resilience, and evacuation routes.

The Local Infrastructure Hub hosted a webinar in June 2023 on developing competitive PROTECT applications and released a resource on winning strategies for PROTECT grant applications available here. The next round of PROTECT Discretionary Grant Program funding is expected to be announced later in 2024.

|

PROTECT Discretionary Grant Types |

|

| Planning Grants | Development of resilience-improvement plans, resilience planning, predesign and design activities, capacity-building activities, and evacuation planning and preparation initiatives |

| Resilience Improvement Grants |

To enhance the resilience of existing surface-transportation infrastructure by improving drainage, relocating roadways, elevating bridges, or incorporating upgrades to allow infrastructure to meet or exceed design standards

* This case story discusses Philadelphia’s Resilience Improvement Grant |

| Community Resilience and Evacuation Routes | To enhance the resilience of evacuation routes or to improve their capacity and add redundant evacuation routes |

| At-risk Coastal Infrastructure | To protect, strengthen, or relocate coastal highway and non-rail infrastructure. |

Considerations for municipal leaders

- What are the surface transportation assets at risk due to natural hazards, and what are those specific risks?

- How does this infrastructure support local community needs, including access to essential services, transportation links, and economic activities?

- What nature-based solutions can be utilized to enhance infrastructure resilience and minimize environmental impact, such as wetland restoration and riverbank protection?

- How can workforce development and local supplier programs be integrated into infrastructure projects to provide training and employment opportunities, especially for underrepresented groups?

- How can local stakeholders and communities be engaged from the beginning of the project to ensure their needs and concerns are addressed?

Bridge Sustainability in NW Philadelphia

Project Leadership:

- Mayor Cherelle Parker

- Lily Reynolds, Director of Federal Infrastructure Strategy

- Ryan Sen, Acting Chief Bridge Engineer

Location: City of Philadelphia

Focus: Climate

Overview: Philadelphia’s Strategic Approach to BIL

The City of Philadelphia has sought to leverage the full potential of the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, by competing for funds to upgrade and maintain physical infrastructure and to use the projects to support workforce and local business development. In October 2022, the City of Philadelphia appointed its first Director of Federal Infrastructure Strategy, Lily Reynolds, to lead a cross-departmental Infrastructure Solutions Team (IST). Their strategy, focused on maximizing local impacts while aligning projects with federal goals, has been critical in the City’s success in securing over $500 million in recent years for infrastructure projects in and around Philadelphia from the BIL and Inflation Reduction Act.

IST is led by the City’s Office of Transportation and Infrastructure Systems (OTIS), with support from other departments including the Department of Streets, Philadelphia Water Department, Procurement Department, Department of Commerce, the Office of Economic Opportunity, and the Department of Planning and Development. The cross-departmental organizing strategy has allowed Philadelphia to effectively leverage the full potential of the BIL, maximizing local impact.

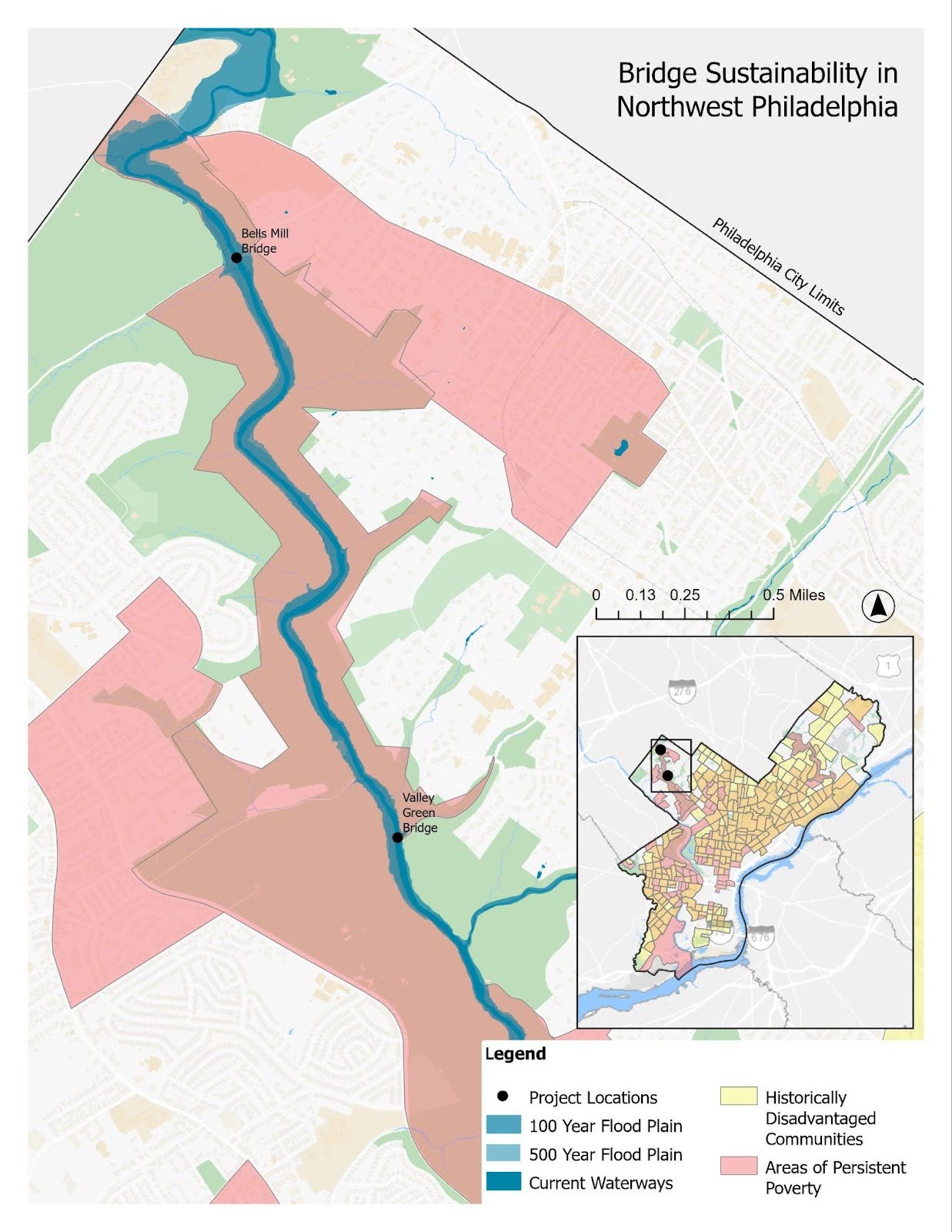

This case story looks at how this comes to ground at the project level through a discussion of Philadelphia’s $14.25 million PROTECT discretionary award for the rehabilitation of two bridges (Bells Mill Road and Valley Green Road Bridges) crossing the Wissahickon Creek in Northwest Philadelphia. Built in the 1800s, the two bridges provide pedestrian and motor access to Wissahickon Valley Park, as well as motor access to Chestnut Hill Hospital and are critical to the local transportation network.

The Project: Northwest Philadelphia Bridge Sustainability

The Bells Mill Road Bridge, built in 1820, is a historic landmark. Since its construction, it has been a critical crossing point of Wissahickon Creek. While there have been several maintenance and repair efforts in the 200 years since its initial construction, it has never undergone a complete rehabilitation. Its proximity to the creek, along with the Valley Green Road Bridge, leaves it vulnerable to storm and flooding events as well as structural degradation. The bridge’s superstructure and substructure are exposed due to water damage, and floodwaters and fast-moving debris from future severe storms will continue to erode bridge structural supports, weaken structural integrity, and hasten deterioration to the point where the bridge becomes unsafe and the City must close it to all traffic. Both the Bells Mill Road Bridge and Valley Green Road Bridge have been rated in poor condition by PennDOT. The project will reduce the bridges’ sensitivity by bringing both structures back to a state of good repair and enhance features at, below, and above the waterline. These enhancements will increase resilience in the face of greater streamflow and more frequent flooding events, both of which are expected to become heightened risks due to climate change.

Without comprehensive rehabilitation work, the two bridges have a remaining useful life of approximately 6-10 years. This is a deep concern for community leaders given that Bells Mill Road Bridge provides the only transportation link between the Upper Roxborough and Chestnut Hill neighborhoods – including access to Chestnut Hill Hospital – while the Valley Green Road Bridge serves as one of the only vehicle access points to central Wissahickon Valley Park and its many pedestrian and cycling trails. Both bridges are critical access points for the park and its amenities, cherished assets for the community.

Additionally, the Bells Mill Road Bridge is an essential link within Northwest Philadelphia’s traffic network. Its space within the Wissahickon Gorge and areal topography leaves users without a convenient alternate route if the bridge were to go out of service and, depending on the alternate routes, detours can add up to seven miles to the trip.

Pre-engineering design work is expected to begin this year (2024) and continue into next year (2025), with construction for both projects set to begin in Summer 2026 before estimated completion in November 2027.

|

Wissahickon Valley Park Acquired by the Fairmount Park Commission in 1868, Wissahickon Valley Park is an 1,800-acre urban oasis of dramatic scenery, dense forests, rugged trails, and free-flowing streams, including over 55 miles of wooded biking, hiking, and equestrian trails through a deep gorge around the creek. In 1920, the wide road paralleling the creek was closed to vehicular traffic and became Forbidden Drive – a key part of Philadelphia’s Circuit Trails Network, connecting with other regional multi-use trails. The low-lying gravel road follows the creek, offering hiking and cycling opportunities. Wissahickon Park is one of the largest urban parks in the U.S. and designated as an Audubon Important Bird Area. The Park includes historic stone bridges and huts dating back to the Works Progress Administration era of the 1930s and 40s. |

Ryan Sen, acting Chief Bridge Engineer for the City’s Department of Streets, noted that the two bridges funded through this award have been slated for repair efforts for several years and that because of their precarious footings, they must be inspected after large storms. Given the similarities in these bridges and their proximity to one another, Sen noted the City’s interest in having a contractor mobilize on both sites at the same time. Given this, the City decided to bundle the bridges for this application to maximize its competitiveness and impact for the community.

Community Engagement and Impact

Community Engagement

Community and stakeholder engagement is a critical next step in the project, particularly in the Northwest Philadelphia area. This will involve engaging with Friends of the Wissahickon, local neighborhood groups, Chestnut Hill Hospital, emergency responders, and a local retirement community, amongst others. Sen noted that given the regular inspections of the bridges, Philadelphia’s Department of Streets has been able to develop relationships and build trust with local stakeholders. The City plans to leverage these existing relationships throughout the community engagement process.

The City’s Office of Transportation, Infrastructure, and Sustainability (OTIS) will leverage its years of community engagement experience to proactively solicit input from community stakeholders to guide the project and keep them informed as the project develops. As noted in their grant application, “in this sense, the City is planning with, not planning for, the Northwest Philadelphia neighborhoods.”

|

OTIS Guiding Principles for Community Engagement

* Responses from OTIS staff have been edited for length and clarity. |

Community Impact

The bridges play an important role in the community, providing connections to and through Wissahickon Valley Park for community members in disadvantaged census tracts. According to the Council on Environmental Quality’s Climate and Environmental Justice Screening Tool, the project is located in a disadvantaged community that faces extreme environmental, health, and societal impacts and is considered high risk for climate related disasters. Rehabilitating the two bridges will improve quality of life for disadvantaged communities by enhancing their access to green space and recreational activities. For many local residents without a car, this park is among the few outdoor destinations conveniently accessible via public transportation, including proximity to regional rail and bus routes.

|

Climate and Environmental Justice Screening Tool The Climate and Environmental Justice Screening Tool (CEJST) is an interactive map which uses datasets that are indicators of burdens in eight categories: climate change, energy, health, housing, legacy pollution, transportation, water and wastewater, and workforce development. The CEJST uses this information to identify communities that are experiencing these burdens and identify those that are disadvantaged because they are overburdened and underserved. Federal agencies use the tool to help identify disadvantaged communities that will benefit from programs included in the Justice40 Initiative, which seeks to deliver 40% of the overall benefits of investments in climate, clean energy, infrastructure, and related areas to disadvantaged communities. |

The City will also collaborate with Wissahickon Restoration Volunteers to ensure that the bridge rehabilitation is sustainable and has minimal negative environmental impact. The Department of Streets will work to incorporate nature-based solutions so that there is minimal disruption to the surrounding valley from the bridge rehabilitation. The project will include restoration of wetlands both in the vicinity of the bridges and along the creek’s tributaries to reduce water volume during extreme weather events.

During the design phase, the project team will also explore the possibility of utilizing native material revetments, or retaining walls, to strengthen stream bank resiliency and promote the growth of protective vegetation. Altogether, these nature-based solutions will help bring the bridge structures to a state of good repair and enhance resiliency by reducing the speed and intensity of the creek’s flooding and fast-moving waters. With these repairs and enhancements to the natural environment, the bridges’ lifespans are expected to be increased by several decades.

Leveraging BIL investments for Workforce Development

Philadelphia’s cross-departmental efforts, driven by the Infrastructure Solutions Team (IST), has enabled Philadelphia to effectively leverage BIL opportunities for investments in local workforce development and business support. The City has included funding for new workforce training programs through BIL opportunities like RAISE and Reconnecting Communities and Neighborhoods. Beyond funding, the City recently announced its new Geographic and Economic Hiring Preferences (GEHP) for select public works contracts, which establishes hiring goals for apprentices and journeyworkers from disadvantaged zip codes. Accelerator for America recently highlighted Philadelphia’s winning workforce strategies in a newsletter encouraging more communities to include workforce training programs in their BIL applications.

The work going into this PROTECT-awarded project provides an opportunity for the City to utilize the tools and strategies developed to support workforce development and business support offerings in infrastructure sectors. The City has had success utilizing both pre-apprenticeship and registered apprenticeship programs that provide competitive wages and ensure high-quality training and work standards. The City will also continue to use other proven workforce skill training programs like PennDOT’s On-the-Job program.

In April 2024, the Biden-Harris Administration designated Philadelphia as one of four new White House Workforce Hubs, highlighting the success of the City’s funding strategy. Led by OTIS and the Department of Commerce, in partnership with the U.S. Department of Transportation (USDOT) and Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the Workforce Hub will work to increase access to quality training and jobs connected to these historic federal investments. The City is taking a strategic approach to align quality workforce training with public works projects that include Geographic and Economic Hiring Preferences.

The City’s Workforce Hub and hiring preferences will leverage partnerships that support the worker transition from pre-apprenticeship to Registered Apprenticeship Programs. The City of Philadelphia’s Rebuild initiative promotes diversity and economic inclusion by supporting minorities and women with new pathways to skilled trade union apprenticeships. Since its inception, there have been 94 graduates, with 67 going on to work as an apprentice or in construction roles. Over 90% of graduates are individuals of color. Additionally, the Department of Streets has the Philly Future Track program, which seeks to engage at-risk young adults in a 6-12 month paid program to perform meaningful public service work. The Department of Streets’ 2023 cohort was their largest ever, with over 200 participants. Participants who successfully complete the first part of training, focused on supporting the Street Light Improvement Program, will then have the opportunity to apply for and be assigned to a specific occupational track. Successful completion of the occupational track may lead to full time, City civil service employment.

In addition to its own workforce training programs, the City engages with construction and infrastructure pre-apprenticeship programs throughout Philadelphia to prepare workers for good-paying careers and ensure labor supply for the hundreds of millions in federally-funded infrastructure projects that are upcoming.

Altogether, the City’s holistic workforce development approach, which invests in quality training programs, with BIL support, prepares workers for projects that then have geographic and economic hiring preferences, providing a path for underserved individuals to good infrastructure jobs.

Supporting Woman- and Minority-owned Businesses

Beyond their workforce development programs, the City is also making efforts to promote historically underutilized businesses (HUBs) in construction and infrastructure-related sectors. While the City is successfully expanding public works opportunities through BIL and IRA funding, many small and minority businesses lack the necessary capacity to engage in these upcoming public works projects. In an effort to remove these barriers the City has implemented a public/private partnership with three non-profits: The Economy League of Greater Philadelphia, Urban League of Philadelphia, and The Enterprise Center to form SupplyPHL. SupplyPHL supports diverse procurement in two ways: by providing business advisory services and access to capital, and by facilitating the necessary relationships to secure and successfully complete for contracts. Additionally, it serves as a long-term partner to ensure firms continue to grow and remain successful by offering continuous access to existing services and networks.

Also, the City is in the process of creating an Owner Controlled Insurance Program (OCIP) for public works projects procured by the City with costs over $75 million. This allows the owner of the project, the City, to provide the necessary insurance coverage for contractors and subcontractors, mitigating barriers to entry for many firms relating to the cost of bonding. The OCIP can provide smaller businesses with the ability to participate in larger projects without having to carry higher insurance coverage. In addition, OCIPs can have benefits for the City as the project owner, such as better insurance protection for both the owner and contractors covered by the OCIP, lower overall insurance costs, and centralized safety program requirements. The IST is currently working with the City’s Risk Management Division to identify upcoming projects to participate in an OCIP, including bundling multiple smaller projects together, thus expanding the reach of the OCIP to smaller projects as well.

In their PROTECT application, Philadelphia explicitly noted that the procurement work for this project will prioritize local businesses as well as women- and minority-owned businesses.

Project Funding

In addition to the $14.25 million awarded to Philadelphia from PROTECT, the City is providing a $3.57 million match for pre-design and construction that they plan to source from the City’s capital budget (note: a local match is required for resilience grants, but not for planning grants).

PROTECT formula funds are apportioned to states by the FHWA alongside other highway formula funding programs, and administered by the requisite state agency.

Conclusion

Through the City’s pragmatic, cross-departmental organizing efforts, Philadelphia has successfully competed for over $500 million in grant funding, with the aim of reaching $1 billion in competitive awards by 2026. Not only have they seen success in pursuing and capturing these awards, but they are also leveraging those awards to promote inclusive growth by supporting workforce development and business formation and growth.

When asked about the factors contributing to their success in competing for grant funding, the City staff team noted three: (1) their efforts to match local infrastructure needs to the grants’ focus areas, (2) emphasis on how their project meets the needs of local communities, including areas of persistent poverty, and (3) incorporation of strong workforce development and diverse procurement goals in the project implementation plan. Altogether, these three factors allow Philadelphia to tell a compelling story in their grant application and ensure that they deliver equitable impacts alongside the infrastructure investments.

Accelerator for America would like to thank Drexel University Nowak Metro Finance Lab for their partnership in production of this case story for the Local Infrastructure Hub.