Reconnecting Communities Pilot Overview

The Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) established the $1 Billion Reconnecting Communities and Neighborhoods Grant Program as the first-ever federal program dedicated to reconnecting communities that were previously cut off from economic opportunities by transportation infrastructure. The program includes both planning and capital grants to support projects that restore community connectivity through the removal, retrofit, mitigation, or replacement of eligible transportation infrastructure facilities. For FY 2022, the BIL allocated up to $198M for the program:

- $50M for community planning grants

- $148M for capital grants

USDOT announced the first round of awards, totaling $185M in February 2023; this included six capital grants and 39 planning grants.

The Downtown Revitalization Project

Overview

Project Leadership:

- Mayor David Anderson

- Rebekah Kik: Assistant City Manager, City of Kalamazoo

- Christina Anderson: Deputy Director Planning and Economic Development, City of Kalamazoo

- Dennis Randolph: Traffic Engineer, City of Kalamazoo

Location: City of Kalamazoo

Focus: Economic Mobility, Racial Equity

Other Funding Sources:

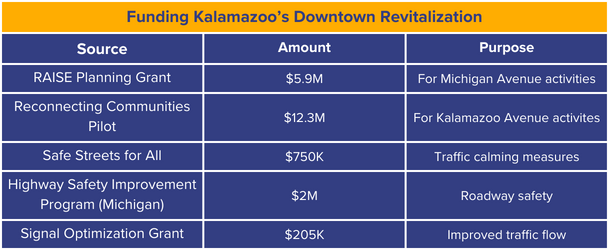

The list below identifies grants received by the city that are being put towards the Downtown Revitalization project: .

- $5.9M RAISE planning grant, for Michigan Ave

- $12.3M Reconnecting Communities Pilot Grant, for Kalamazoo Ave

- $750K Safe Streets for All planning and demonstration grant

- $2M State Highway Safety Improvement Grant (from the state)

- $205K Signal Optimization Grant (from the state)

This case story highlights Kalamazoo’s Downtown Revitalization project, which will convert former state highway routes that run through the downtown, and accompanying one-way streets, into all two-way complete streets, reconnecting the city’s predominantly Black neighborhoods with Downtown Kalamazoo and creating a more bike and pedestrian friendly transportation network.

The Downtown Revitalization project will transform Kalamazoo and Michigan Avenues from one-way high speed traffic corridors into more inclusive pedestrian, bicycle, and transit friendly two-way streets, fostering safety, mobility, and community connection while addressing historical disparities driven by redlining practices.

In addition to Kalamazoo and Michigan Avenues, the Downtown Revitalization project will also include conversions of several other one-way streets in the city, and provide for additional street and physical infrastructure upgrades, in support of the city’s comprehensive network and complete streets approach.

Kalamazoo Avenue reconstruction and two-way conversion is expected to be complete in 2026, followed by Michigan Avenue in 2028. Ransom Street’s conversion to a two-way is expected to be complete this year, with other neighborhood streets, including South Street, Lovell Street, and Main Street slated to follow after Michigan and Kalamazoo Avenues, all of which will take the project through 2032.

* This case story will focus on the planned work for Kalamazoo and Michigan Avenues, for which the city received federal funding via the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL).

What are Complete Streets?

Complete Streets is an approach to planning, designing, building, operating, and maintaining streets that enables safe access for all people who need to use them, including pedestrians, bicyclists, motorists and transit riders of all ages and abilities. While Complete Streets is an approach, it does not prescribe a singular street design. As such, Complete Streets provides space for rural, suburban, and urban communities to safely design streets in a way that meets the needs of their residents and aligns with their local context. Complete Streets may include sidewalks, bike lanes (or wide paved shoulders), special bus lanes, comfortable and accessible public transportation stops, frequent and safe crosswalks, median islands, accessible pedestrian signals, curb extensions, narrower travel lanes, roundabouts, and more.

From Smart Growth America

Unpacking the Challenges: Community Safety and Business Concerns

In 1965, Michigan Department of Transportation (MDOT) changed Kalamazoo Avenue, Michigan Avenue, and other streets in the city’s downtown from two-way streets to one-way streets to help drivers get through the city and onto the interstate more quickly. While this change successfully reduced the number of stops made by drivers and increased average speeds by 11 miles per hour, achieving MDOT’s primary objective, it came at the expense of residents of adjacent neighborhoods. As Dennis Randolph, the city’s traffic engineer, said the shift “made the downtown less accessible to surrounding neighborhoods, and created a hostile environment for anyone not in a car.” Impacted neighborhoods include the predominantly Black and historically redlined Stuart and Northside neighborhoods, which were divided and disconnected from the city’s core business district by the resulting high-speed, high-capacity one-way streets. In addition to disconnecting these neighborhoods from the core business district, the change hindered economic growth and caused traffic safety issues for drivers and pedestrians.

“Kalamazoo Avenue served as a moat right between halves of the [Stuart] neighborhood including the school on one half and houses on the other” – Christina Anderson, Deputy Director for Community Planning and Economic Development

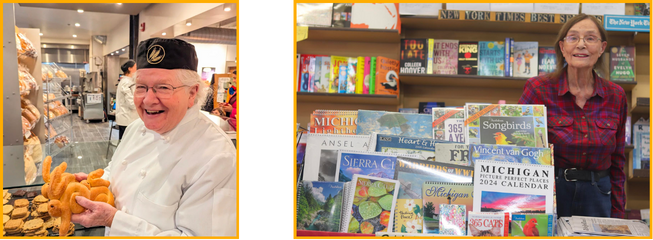

Sarkozy Bakery & Cafe, was opened by Judy Sarkozy, a local baker, on Michigan Avenue in 1978 and was designed to entice pedestrians with views of treats through large windows. 40 years later, the vision of a pedestrian-driven customer base has not materialized, “a consequence of a downtown that just wasn’t designed for her customers” as Sarkozy recently said, further noting that Kalamazoo needs “a friendly city area instead of businesses on a highway.”

Similarly, Dean Hauck, owner of the Michigan News Agency, located half a mile from Sarkozy Bakery on Michigan Avenue, noted that the business was “practically destroyed” with the change on Michigan Avenue as patrons have a difficult time accessing the store. The immediate impacts for the Agency were clear as the business, which opened almost 20 years prior, saw half as many people and up to $300 less in daily revenue. These themes have been reiterated by other local business owners who have described the one-way streets “as speedways rather than access points for commerce.”

The city’s most recent master plan, Imagine Kalamazoo 2025 (IK2025), validated these positions, finding that “the one-way pairs in Downtown [Kalamazoo] continue to impart the greatest challenge in Downtown for those that live, work, and play.” Furthermore, retail and placemaking focused studies for the master plan found that the solution to removing a major barrier to retail growth would be to solve the “fast traffic, difficult navigation, and pedestrian crossing issues on the remaining one-way streets.”

The economic cost of one-way streets has been verified in studies that suggest that motorists often overlook storefronts on one-ways, and one-way streets can reduce storefront exposure to drivers since only one side of the building is exposed to drivers.

Furthermore, state-reported crash data illustrates the dangers of one-way streets like Kalamazoo and Michigan Avenues; one-way roads and intersection approaches on urban arterials have more crashes than collector roads, and these are of a higher severity given the higher percentage of trucks and complex traffic mixes on arterials. A third study, in a different geography, found that the injury rate was 2.5 times higher on one-way streets than on two-way streets, and 3 times higher for children from the poorest neighborhoods than those from wealthier neighborhoods.

While the paired Michigan and Kalamazoo Avenues only account for 1.5% of the city’s roadmap, they account for a disproportionate 7% of all crashes in the city over the last decade. According to Kalamazoo’s traffic engineer, Dennis Randolph, a local study found that there are 300 to 400 car crashes annually on Kalamazoo’s roads alone – many of which are more similar to the style of crash characteristic of arterials rather than those on city streets, given the design and frequent high speeds on Kalamazoo and Michigan Avenues.

Pre-Development: Planning and Community Engagement

In the decades since the 1965 conversion, Kalamazoo has frequently explored converting Kalamazoo and Michigan Avenues back to two-ways that are safer and more conducive to the urban environment. However, the two streets (along with several others in the city) were under the jurisdictional control of the MDOT as designated state routes. While the city’s goal was to develop a robust network of roads conducive to local traffic, the state historically focused on developing high-capacity corridors that can facilitate faster movements. Since the early 2000s, disagreements between the Kalamazoo and the regional MDOT office about the role of the roads through downtown Kalamazoo made it difficult to find common ground. The engagement process for IK2025 helped to demonstrate the community’s views on the matter.

Over 16 months, the IK2025 process engaged 4,000+ diverse community voices – at open houses, community picnics, tables at regular community events like Art Hop and Lunchtime Live, and online surveys. Through this process, the city also developed and adopted an updated Public Participation Policy and Community Engagement Guide and Toolkit to support future outreach and engagement by the city, which is informing continued engagement today.

The IK2025 master plan laid out a vision for downtown life that reflected the goals laid out in the strategic vision and took a holistic approach to the street network in Downtown Kalamazoo; specifically, the plan looked at –

- Aligning land use and transportation;

- Creating inviting public places for movement, gathering, and commerce;

- Ensuring mobility for all users, regardless of modality, ability, race, income, etc.;

- Improving community safety; and,

- Strengthening the links between economic vitality, housing, and transportation.

“Streets are both public spaces used by all users and network systems helping transport people and goods. It’s vital to the fabric of Kalamazoo and integral to the Strategic Vision implementation to look at the network holistically.” – Kalamazoo Strategic Vision

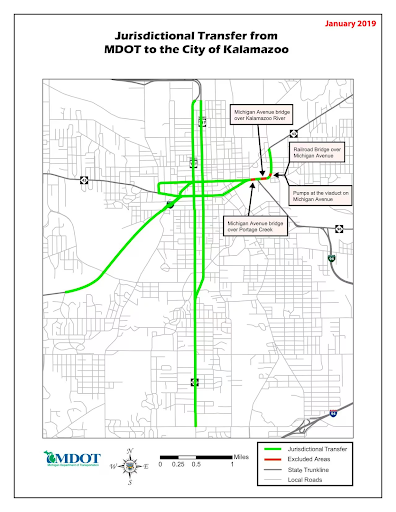

After trying unsuccessfully to find a path forward, in 2018, MDOT staff in the regional office began to work with the city to transfer all downtown trunkline highway routes to local control. This culminated in January 2019, when the Kalamazoo City Commission approved a memorandum of understanding with MDOT, after working with the state attorney general, MDOT, city attorney, and other parties to come to an agreement that transferred control for 12.3 centerline miles of state-owned roads, including Michigan and Kalamazoo Avenues, to the city. The agreement included a $11.7M lump sum payment to the city to cover major repairs on the roads for the next 10 years, costs that were previously borne by the state. With the transfer, the City of Kalamazoo and local residents were given full decision-making power over the design and operations of streets leading into and around the city’s downtown, enabling them to implement the vision called for in IK2025.

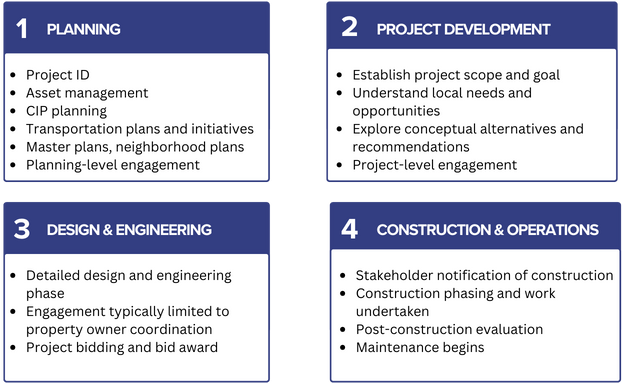

The city then undertook another engagement process focused on the Street Network Design Project, this process had two goals: (1) confirm the community’s wishes for slower streets with conversions for two-way traffic which would better serve all road users, and (2) work with traffic engineers to study new street designs to understand changes in traffic patterns and intersections. Through the project, the city developed a new street design manual, that outlines the life of a complete street project. The city’s work in the coming years for the Downtown Revitalization project will be guided by the manual and its underlying principles.

Throughout these engagement processes, city leaders affirmed that zoning regulations did not align with what was actually in neighborhoods, and this became a key component of their planning. Christina Anderson and her team in the city’s Community Planning and Economic Development office worked to update zoning ordinances to align the regulations with the IK2025 master plan. One example of the zoning conflicts was evident in Northside, where there was an outdated manufacturing zone that limited the zone’s use. The city changed this to ensure that the zoning ordinances would support mixed use developments that aligned with what was actually in the neighborhood. These corrections to the zoning ordinances also provided an opportunity to resolve zoning conflicts that limited new housing opportunities.

Public input and engagement continues to play a major role in shaping discussions and plans on this project. Feedback from the community has led to further consideration of traffic-calming measures, pedestrian infrastructure, and expanded bike lanes. Dennis Randolph, Kalamazoo’s traffic engineer, noted that a key to the success of their community engagement processes was that they “have a team of folks that have really bought into [how can we make this better], not ‘how can I protect my original design,” illuminating the team’s adaptability in responding to feedback from the community. In maintaining humility throughout the process, and focusing on project outputs rather than integrity to the original design, Kalamazoo’s project leadership demonstrated agility that enabled them to innovate throughout the project and will continue doing so in the coming years.

Phases of Street Design Process for Public Projects

Pilot Projects and Construction

Since the jurisdictional transfer and throughout their planning processes, the city has begun implementing several pilot projects. For example, on Michigan Avenue, the street was downsized from six lanes to two lanes, enabling the additional pavement to be transformed into on-street parking and a two-way bicycle track. In October 2023, the city installed bicycle traffic signals along the two-way track on Michigan Avenue, as well as on Westnedge Avenue and Park Street at Michigan and Kalamazoo Avenues.

These pilot projects, launched just in Fall 2023, have already seen uptake by the city’s bicycle riders and reduced crashes by 33% in the first two months, all without having an adverse impact on the flow of traffic – Assistant City Manager, Rebekah Kik, recognized that the great improvement in safety outcomes came at a miniscule cost to travel times, adding only 26 seconds on their travel time metric.

Dennis Randolph, the city’s traffic engineer, also discussed a $205K signal optimization project that aims to optimize 41 traffic signals in the city – reducing wait times while preventing backups, delays, and other traffic problems. These pilot projects not only allow the city to experiment with traffic calming measures that can be adopted throughout their transportation network, but they also give the city opportunities to experiment, gather feedback on innovations, and gather more data that can strengthen future grant applications. Delivering in the short-term is important for maintaining community support as it allows the city to serve communities immediately and demonstrate what is coming at a grander scale in the long-term.

Looking at long-term projects, the city continues to work towards the full conversions on the prominent Michigan/Kalamazoo Avenue pair with Kalamazoo Avenue up first. The Kalamazoo Avenue reconstruction and two-way conversion is expected to take place from 2024-2026, followed by the Michigan Avenue reconstruction and two-way conversion from 2026-2028. Following that work, South Street, Lovell Street, and Main Street will be converted to two-way streets in the Downtown in the subsequent years. Ransom Street, which runs parallel to Kalamazoo and Michigan Avenues in the Northside neighborhood, is undergoing repair work now to better serve its community with work expected to be complete in 2024.

The sequencing plan results from higher traffic volumes on Kalamazoo Avenue and matches with the ongoing work on Ransom Street that is connected to the historic redlining in the Northside neighborhood. Furthermore, Kalamazoo Avenue currently splits the Stuart neighborhood in the city’s west side, and prioritizing this street will help immediately better serve that community. Altogether, completing Kalamazoo Avenue first will serve purposes related to traffic flow and community/economic objectives.

Project Funding

Although the Kalamazoo Avenue conversion has been described as a “cornerstone project” for the city’s downtown, it is just one component of the broader downtown revitalization project to reconnect Kalamazoo. In this effort, Kalamazoo is utilizing a variety of federal funding programs authorized under the BIL, as well as state resources.

Kalamazoo also received about $11M from the state to support maintenance costs for the roads that were transferred to local control. The city is also applying for a PROTECT grant to support aspects of the project related to the development of a new events center downtown.

These funds are going towards planning-related activities for the Downtown Revitalization project, including pilot projects for different traffic calming measures and active transportation upgrades, as well as construction work for Kalamazoo Avenue. The city previously used American Rescue Plan Act funding sources for public outreach and engagement.

Community Impact

The city’s full plans for Kalamazoo’s downtown, inclusive of all street conversions planned, will address issues that have worsened transportation safety over the years in Kalamazoo, enable investments in the city’s public transit infrastructure, and provide for bicycle tracks that will induce more bike-riders to utilize the active transportation mode. Additionally, the project will eliminate the physical barriers that have divided the Stuart Neighborhood and separated the Northside community from Downtown Kalamazoo – reconnecting historically Black communities with the economic opportunities in the core business district.

Quantitatively, the Kalamazoo Avenue conversion alone, funded by the RCP capital grant, will see a project net value of $7.6M and a benefit-cost ratio of 1.44, meaning that every $1 invested in the project yields benefits valued at $1.44, these benefits are mainly derived from safety improvements throughout the corridor. The benefit-cost analysis was conducted as a requirement of their RCP grant application, and done in accordance with the benefit-cost methodology outlined by USDOT. This expected benefit is not inclusive of the positive impacts on economic development for the surrounding neighborhoods. According to the Downtown Kalamazoo Retail Market Analysis, the conversions throughout Kalamazoo will add an estimated $20M in retail revenue and 52K square-foot in leasing space in the area by addressing “non-market conditions” impacted by the current road design.

The RAISE planning grant for the Michigan Avenue conversion will help to fund a cost-benefit analysis that will quantify the value of all costs and benefits associated with Michigan Avenue’s conversion.

Beyond the surface improvements, the project is also providing an opportunity to upgrade outdated utility infrastructure that is currently under the road. They have applied for additional funding opportunities that would provide funding for the city to improve existing stormwater infrastructure, creating additional lots for future development within the areas impacted by the street conversion.

Conclusion

Driven by residential shifts out of the inner core of cities towards the suburbs, highway and road developments of the mid-20th century had a disastrous effect for many of the communities that they went through, as is evident in Kalamazoo’s downtown areas. The unprecedented funding authorized through the BIL, including but not limited to the new Reconnecting Communities program, is providing opportunities for cities to revisit the remnants of past infrastructure investments and revitalize communities.

As Alex Wells, co-owner of Sarkozy Bakery noted, “Kalamazoo has a remarkably intact downtown, and the traffic isn’t allowing us to take full advantage of it,” these investments are enabling the city to change that narrative.

Accelerator for America would like to thank Drexel University Nowak Metro Finance Lab for their partnership in production of this case story for the Local Infrastructure Hub.